An aphorism is a concise, memorable expression of a general truth or principle, usually no longer than a sentence. Aphoristic literature has been popular with philosophers throughout the Western literary tradition, from the earliest times to more recent examples in the work of Vico, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. Educators too have since classical times recommended the use of aphorisms in the instruction of students “in certain rudiments of oratory” (Quintillian, Institutio Oratoria 1.9), and they can continue to serve similar ends in education today. Concise and self-contained while at the same time rich in meaning and implications, aphorisms provide great prompts for rich conversations around the open-ended big questions of life.

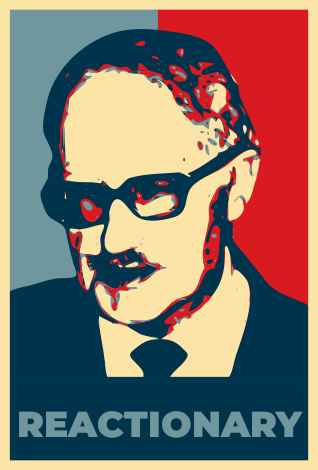

Which brings us to the 20th century Colombian philosopher Nicolás Gómez Dávila, whose life’s work consists almost entirely of aphorisms. He broached a broad range of topics including literature, philosophy, religion, the arts and culture, always from a perspective of reaction against the moral and spiritual decline he saw in the modern world. If his aphorisms have any value as educational resources in addition to those mentioned above, it is that they address contemporary concerns while being based on the timeless depths of tradition.

Gómez Dávila was born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1913. From the age of six to twenty-three he lived in Paris where he attended a Benedictine college and was homeschooled for some time due to pneumonia. Largely an autodidact, he was fascinated by literature, history, theology, philosophy and classical languages, and spent most of his adult life in his personal library which held a collection of over 30,000 books in Spanish, French, Italian, German, English, Portuguese, Latin and Greek. He possessed a vast knowledge of the Western literary canon and, although he never attended university himself, he helped establish the Los Andes University in Bogotá in 1948. Gómez Dávila largely refrained from political activity and was critical of both left-wing and right-wing political positions. He supported president Alberto Lleras Camargo's role in bringing down the Colombian dictatorship in 1958, but subsequently declined the position of chief advisor to the president. He also declined an offer in 1974 to become the Colombian ambassador to London. He died in Bogotá in 1994.

Gómez Dávila’s best known work is a collection of aphorisms titled in their original Spanish as the Escolios a un texto implícito (Scholia to an implicit text), published in three volumes from 1977 to 1992. Scholia are a type of scholarly footnote found in the margins of many mediaeval european manuscripts (singular scholium). Gómez Dávila’s scholia or aphorisms are often micro-summaries of works he had read, conclusions drawn from those works, or judgments on them. Despite the diversity of topics addressed, the Escolios are consistently critical of modern liberal and progressive ideologies, to which Gómez Dávila attributes the moral and spiritual decline of the modern world. The Escolios began to receive critical attention only in his final years, initially in Italy and Germany, followed by the wider Spanish-speaking world. Translations into English unfortunately remain fragmentary.

While Gómez Dávila was comfortable with the label “reactionary”, his reaction was not narrow-minded traditionalism aligned with some utopian political position. Rather, his was a broad project of preserving cultural values and heritages within the world. As a traditional but undogmatic Catholic, he had a deep appreciation for what he considered to be the classical roots of the Roman Catholic church. He considered the Second Vatican Council a problematic compromise with the modern world, and lamented the destruction of the Latin liturgy in the wake of the council.

Gómez Dávila understood modern atheistic democracy less as a political fact than as a kind of anthropotheist religion in which modern man has forsaken the divine order and begun to worship himself instead. Like Plato he rejected the democracy of the mob in which foolish, dangerous and sometimes horrific ideas are upheld simply because they have a large number of supporters. Gómez Dávila predicted that by the late twentieth century the mere act of reading would become a “reactionary” pursuit, and that while knowledge and reading had always shared a “sacred marriage”, post-modernity had destroyed the bond between education and reading. The only option left for readers is to “go underground”, as it were, for knowledge can only be salvaged in works that preserve the “clandestine deposits” of the wisdom of the ages. For the record, in his opinion the greatest of all books he had read was the History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides (460-400 BC), an account of the war between Sparta and Athens.

To conclude, the following examples (with English translations) have been selected from Escolios a un texto implícito (Vol. I and II) by Nicolás Gómez Dávila, translated into Italian from the original Spanish by Loris Pasinato with a foreword by Alessio Mulas, published by Gog Edizioni (Rome 2020):

Gli individui della società moderna sono ogni giorno più somiglianti gli uni agli altri e ogni giorno più estranei tra loro. Monadi identiche che si affrontano con individualismo feroce.

The individuals of modern society are every day more like each other, yet more estranged from each other. Identical monads confronting each other with ferocious individualism. [p540]

…

Tutta la letteratura è contemporanea per il lettore che sa leggere.

All literature is contemporary for the reader who knows how to read. [p51]

…

Tutte le epoche manifestano gli stessi vizi ma non tutte presentano le stesse virtù. In ogni tempo ci sono tuguri, ma solo a volte ci sono palazzi.

All eras share the same vices, but not all produce the same virtues. Every era has hovels, but only occasionally are there palaces. [p187]

…

Gli uomini cambiano meno di idee che le idee di costume. Lungo i secoli conversano le stesse voci.

Men do not so much change ideas as ideas change fashion. Throughout the ages the same voices converse. [p27]

…

Se vogliamo che qualcosa duri, facciamolo bello, non efficace.

If we want something to last, we make it beautiful, not efficient. [p469]

…

La civiltà non è una successione senza fine di invenzioni, bensì il compito di garantire la durata di certe cose.

Civilization is not an endless succession of new inventions, but rather the task of ensuring that certain things last. [p164]

…

La violenza non è sufficiente a distruggere una civiltà. Ogni civiltà muore per la sua indifferenza di fronte ai valori peculiari che la fondano.

Violence is not enough to destroy a civilisation. Each civilisation dies from indifference towards the unique values it was founded upon. [p58]

…

Il mistico è l'unico ambizioso serio.

Only the mystic has serious ambition. [p96]

…

Il mondo che non è sacramentale è insipido.

The world that is not sacramental is insipid. [p46]

…

Tutto è banale se l’universo non è coinvolto in un’avventura metafisica.

Everything is banal if the universe is not part of a metaphysical adventure. [p37]

…

Il mondo, fortunatamente, è inesplicabile. (Cosa sarebbe un mondo spiegabile dall'uomo!)

The world, fortunately, is inexplicable. (What would a world explainable by man be!) [p377]

…

Dobbiamo restituire alla notte la positività che la nostra insufficiente astronomia le nega. Il nostro compito più urgente è quello di ricostruire il mistero del mondo.

We must restore to the night the positivity that our inadequate astronomy denies it. Our most urgent task is to reconstruct the mystery of the world. [p329]

…

La civiltà non consiste nella somma degli oggetti che la compongono come neppure l’uomo consiste nella somma degli organi che lo costituiscono.

Civilisation does not consist of the sum of the objects that make it up, just as a man does not consist of the sum of the organs that make him up. [p350]

…

L’uomo moderno è scandalizzato dai luoghi comuni tradizionali. Il libro più sovversivo nel nostro tempo sarebbe una raccolta di vecchi proverbi.

Traditional sayings scandalise the modern man. The most subversive book of our time would be a compendium of old proverbs. [p133]

…

Il culto dell'umanità si festeggia con sacrifici umani.

The worship of humanity is celebrated with human sacrifices. [p213]

…

In un secolo nel quale i mezzi pubblicitari proclamano infinite sciocchezze l'uomo colto non si definisce per ciò che sa ma per ciò che ignora.

In an age when the advertising media broadcast infinite nonsense, a cultured man is defined not by what he knows but by what he does not know. [p173]

…

Il Progresso alla fine si riduce a rubare all’uomo quello che lo nobilita per potergli vendere a buon mercato quello che lo svilisce.

In the end, Progress is nothing more than robbing man of that which ennobles him in order to sell to him cheaply that which degrades him. [p323]

…

Più che cristiano, forse sono un pagano che crede in Cristo.

More than a christian, I am perhaps a pagan that believes in Christ. [p191]

…

È un cattolico serio solo chi erige la cattedrale della propria anima su cripte pagane.

Only he who erects the cathedral of his soul upon pagan crypts is a serious catholic. [p106]

…

Il paganesimo costituisce per la Chiesa un altro Antico Testamento.

For the Church, paganism is another Old Testament. [p131]

…

La Chiesa cattolica fu l'ultima delle creazioni del patriziato romano.

The Catholic church was the final creation of the Roman aristocracy. [p144]

See also: Radical Reactionary II (36 aphorisms by Nicolás Gómez Dávila).